Dame Robin White’s retrospective proves that universality is found through distance

Hero/Heroine Online – October, 2022

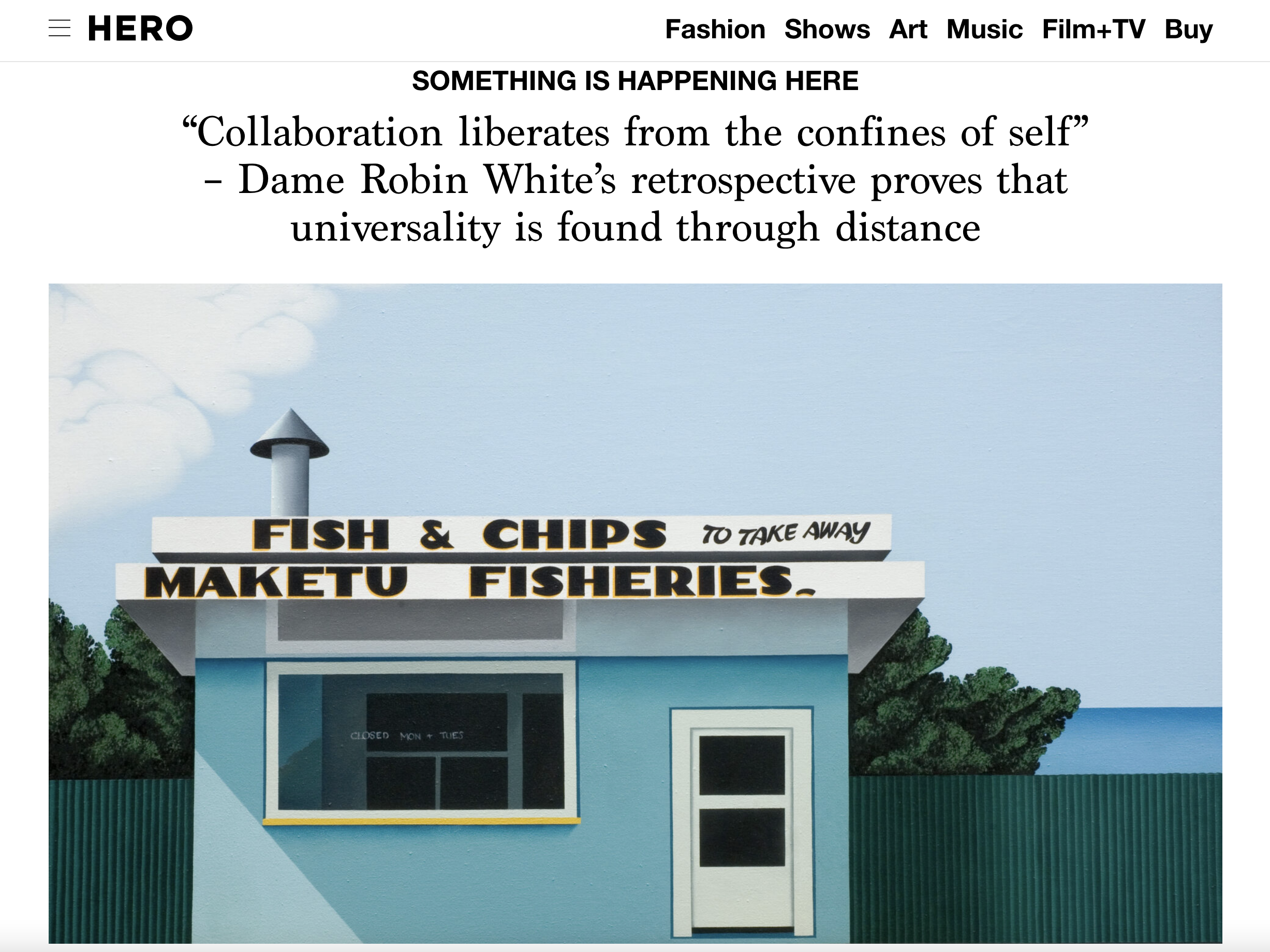

As a celebrated artist from Aotearoa New Zealand, a profound sense of place is tethered to Dame Robin White. When she began working full-time as an artist on the Otago Peninsula in the 70s, her distinctive portraits and landscapes led her to be considered a leading ‘regionalist’, etching a national identity.

But when the painter and printmaker of Pākehā and Māori descent made the leap to a small atoll in the Pacific, with her Baha’i faith, her work took on a more panoramic sense of self. While living with her young family in Kiribati in the 90s, a devastating studio fire also saw her rise to the challenge of working only with the materials available in her local environment, and working more closely with local artists to produce a series of woven pandanus mats.

Since moving back to Aotearoa in 1999, White has continued to learn from collaborators across the wider Pacific – including recent tapa works made with Tongan artists Ruha and Ebonie Fifita, Fijian artist Tamari Cabeikanacea, and a painted panel work with her Japanese friend Keiko Iimura, to name a few.

Now comes an ambitious and much-earned retrospective, Te Whanaketanga | Something is Happening Here, which involves a co-curation between two of New Zealand’s leading cultural institutions, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, supported by a publication bringing together diverse viewpoints. Fifty-four years after her very first exhibition, White shows the same unwavering commitment to not just her art, but how she shares it with others.

Jessica-Belle Greer: Why do you feel now is the right time for a retrospective?

Dame Robin White: I hope having an exhibition that covers the period from when I first emerged from art school right up until the present time will be sufficient to turn the tide of the understanding of the nature of my work – the variety of media, and the different kinds of methods and approaches, especially working collaboratively. There’s an awful lot of nostalgia about the work I did in the 70s, but life has gone on. I have lived in markedly different cultural and social settings which has all found its way into my work. I see it as a really valuable opportunity to give a broader perspective and see the differences, but also to see the connections.

JBG: Collaboration is especially important, and striking, in your more recent works.

DRW: There are a number of things that attract me to that way of working. It offers a broader horizon of possibility, as well as risk. It offers a lot of valuable lessons and develops skills needed way beyond an art practice. Skills needed for contributing to the wider community, to your neighbourhood and to your family like listening and consultation. Above all, it’s making the effort to really form relationships. Collaboration liberates from the confines of self.

“It’s hard to define, but you are constantly confronted by the enormity of the sky and the fathomlessness of the ocean which somehow has a psychological effect.”

JBG: I like the idea of finding unity in diversity, which is tied to your Baha’i faith.

DRW: Ultimately, everything depends on the relationships of the people who are working together. Those of us who are working together come from different core traditional backgrounds, working collaboratively is an example of how all of us need to be, given that we are living in communities becoming more diverse. Sometimes we refer to it as working in the space between cultures and finding out what dynamic is in that space.

JBG: What can the rest of the world learn from the perspective you have gained from working in the Pacific?

DRW: The Pacific is an ocean of islands with quite distinct cultures but there’s something about the ocean itself that affects the way we view our connections with each other. The ocean has been the highway for centuries. It’s been a means of communication for expressing reciprocity and exchange amongst varied and dispersed peoples over a vast area, it’s an extraordinary place. For all the diversity there is a common thread, and I would characterise it as a very strong sense of community. That is what matters most.

JBG: Wherever you are, your artwork has a strong sense of place.

DRW: Wherever one is living, it’s important to ask: What is this place? What is the kaupapa, as we would say, what are the traditions here? What is the correct way to behave? The thing about living on an atoll [like Tarawa in Kiribati] is the culture has evolved in very, very refined ways of behaving. You have limited land space, so the relationship between people and the land is very different. It’s hard to define, but you are constantly confronted by the enormity of the sky and the fathomlessness of the ocean which somehow has a psychological effect. It opens the mind and the heart in ways that seem less constricted, you become ready to embrace and enjoy whatever comes your way. It was beautiful.

“I wish we could change our mindset and see creativity as being a human capacity, common to all.”

JBG: There is this sense that everything has its place in your artwork too.

DRW: I have a memory of Colin McCahon [a renowned New Zealand artist and Robin’s lecturer] at Elam Art School saying something along the lines of: What you do should not be arbitrary. I’ve thought about that a lot. I came to understand there are some things called structure and order. These things form what we call the aesthetic qualities of a work and McCahon would say things like, “To paint is to contrast.” Gradually you start building on your understanding of what these things really mean in practice, by doing the hard work and making many mistakes. What I really respond to are those unseen things within a work that hold it together.

JBG: How do you do that?

DRW: Well, you can do it hit and miss, but that’s not the way I work. I spend a lot of time thinking about that invisible structure. It’s a form of problem-solving, which is in many ways the best part. It also has a lovely connection with the sensitivity to pattern in traditional Pacific art practices. It’s all about contrast, about creating something coherent out of elements that are different but complementary. It was lovely to find a point of similarity and universality that we could rely on in our conversations working collaboratively.

JBG: You’ve talked about the retrospective being a family reunion, bringing various work together.

DRW: It’s a joyful occasion. It’s like when you see your kids after a long time, you ask; “What have you been up to? Who have you met, and what’s been happening in your life?” It’s like I want to ask all my work the same questions. They’ve been out in the world. There are now several generations who have grown up with the same work, and they’ve all had their own experience of it. I think the work somehow carries a richness because of those unknown engagements with people. There’s a buzz about it that I really like.

JBG: Why is it important for younger generations to be involved with art?

DRW: I taught art very briefly [as part of a studentship], and I could see the potential for art to foster a spirit of creativity among all students, but I was frustrated by the way in which it was – and still is – treated as a separate subject matter unrelated to other subjects in the curriculum. I don’t see art as being something for a select few, or as preparation for an elitist occupation. I’m talking about art in a much broader sense as a powerful tool for enhancing every form of learning. I wish we could change our mindset and see creativity as being a human capacity, common to all.

Te Whanaketanga | Something is Happening Here is showing at the Auckland Art Gallery from October 29th to January 30th. It will travel to the South Island in the new year.